Infection control became a prevalent science in the late 1950s, focused on addressing nosocomial staphylococcal infections. By 1999, the focus on infection control began to transform to infection prevention, no longer accepting health care–acquired infections (HAIs) as an unpreventable cost of business. Instead, the focus shifted to the rapid identification of infections, taking timely action to analyze them, and actively participating in the care processes.1

Sixty percent of surgical site infections (SSIs) were estimated to be preventable, using evidence-based measures that have influenced pay-for-performance and quality-improvement goal metrics, according to a study by Ban et al.2 Addressing strategies for the prevention of SSI can include all avenues of patient care and involve all actual and potential participants in the care continuum, from patients and families in the pre- and posthospital settings to hospital and facility administrators to physicians and nurses to laboratory and supply chains to quality and risk management departments. The care continuum does not stop or start at the hospital doors; indeed, it should start in a patient’s home and continue through a hospitalization to the outpatient care centers and back home or to a care facility.

Gwen Borlaug, MPH, CIC, FAPIC, infection prevention epidemiologist and former director of the Wisconsin Division of Public Health’s Healthcare-Associated Infection Prevention Program, notes that surveillance and performance improvement and implementation science are 2 areas infection preventionists (IPs) can provide that support prevention of SSI. Effective prevention of SSIs is based on active surveillance by IPs, then the findings are communicated back to staff and providers, and they use opportunities for education to improve protocols and compliance.3 Anderson et al notes that IPs must have training in SSI surveillance, have knowledge of and the ability to prospectively apply Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and National Healthcare Safety Network definitions for SSIs, and be able to provide feedback and education to health care personnel.4

SSI Statistics, Risk Factors, and Interventions

A 2016 update from the American College of Surgeons and Surgical Infection Society found that SSIs accounted for 20% of all HAIs.2 An infection incidence of 2% to 5% of patients undergoing an inpatient surgery means an estimated annual 160,000 to 300,000 patients in the United States acquire SSIs yearly.2 SSIs increased the length of inpatient hospital stays and potential mortality 2- to 11-fold (77%) primarily because of the infection.2 Patient care costs were not only related to extended inpatient stays but also emergency department visits and a reported 90,000 annual readmissions.4

The CDC classified SSIs by depth and which tissue spaces were involved. According to the CDC, a superficial incision involves only the skin or subcutaneous tissue, whereas a deep incisional SSI involves the deeper fascia or muscular layers. SSIs can also affect organ spaces of any part of the body opened or manipulated during the procedure.4

Risk factors for SSI include intrinsicand extrinsic components. Intrinsic factors include patient-related modifiable and nonmodifiable factors.

Modifiable factors can include the following:

- glycemic control and diabetic status,

- dyspnea,

- alcohol and smoking status,

- preoperative albumin less than 3.5 mg/dL,

- total bilirubin greater than 1.0 mg/dL,

- obesity, and

- immunosuppression.

Nonmodifiable patient factors can include the following:

- increasing age,

- recent radiotherapy, and

- history of skin or soft tissue infections.

- Extrinsic factors include procedure-and facility-related factors.2

- Procedural risk factors can include emergency procedures, increasing complexity, and higher wound classification. Procedural risk factors can also be attributed to preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative factors.

Preoperative risk factors can include the following:

- any preexisting infections,

- inadequate skin preparation,

- inappropriate antibiotic choice and use,

- hair removal methods,

- and poor glycemic control.

Intraoperative risk factors can include the following:

- longer procedure duration,

- blood transfusions,

- breach in asepsis,

- inappropriate antibiotic redosing,

- inadequate gloving,

- inappropriate surgical scrub,

- poor glycemic control,

- amount of supplemental oxygen used with general anesthesia,

- wound closure,

- use of antibiotic sutures,

- intraoperative normothermia, and

- surgical attire by the surgical team.2

- Postoperative factors can include wound care, topical antibiotics, postprocedure antibiotic use, and use and timing of postoperative showering.

Factors related to the facility can include the following:

- inadequate ventilation,

- increased operating room traffic,

- contaminated environmental surfaces,

- and nonsterile equipment.

In addition, prehospital interventions include the following:

- bathing and showering techniques,

- smoking cessation,

- consideration of long-term glucose control,

- methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus screening and decolonization, and

- bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgeries.2

Posthospital interventions can include wound care and SSI surveillance by the surgeon after discharge. Superficial post-SSIs can be managed in the outpatient clinical setting. However, deep- and organ-space SSIs require more acute care, including emergency department visits and hospital readmissions.2

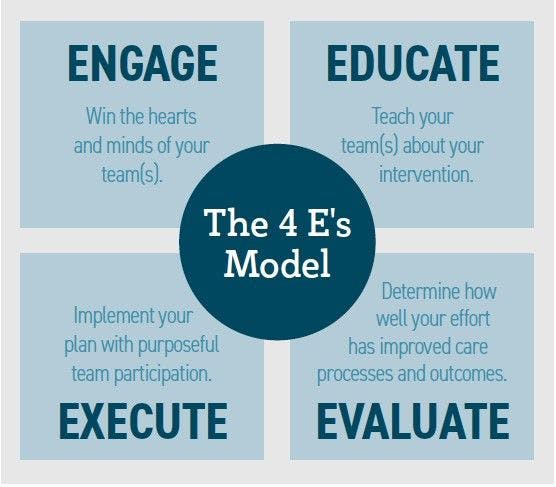

4 E’s: Engage, Educate, Execute, Evaluate

The 4 Es Model or SSI Study Outcomes

In a retrospective study of 125 studies between January 1990 and December 2015, reported that although clinical interventions are evidence-based and able to reduce SSI, they are both not reliably delivered or agreed upon for the best approach on how to improve adherence.5 The study included investigators from The John Hopkins University School of Medicine; Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control; World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean; Cairo, Egypt; Infection Prevention and Control Global Unit, Department of Service Delivery and Safety; WHO; and Ariyo et al.

Data were extracted on a variety of implementation strategies to develop an implementation model called the 4 Es framework: engage, educate, execute, and evaluate.5 The data revealed that evidence-based recommendations were not being followed through at the bedside. The study hypothesized that one possible explanation was that there was limited guidance in translating the evidence-based recommendations into applicable practices at the bedside.

The study focused on developing multiple strategies to translate, educate, and engage all levels of care from surgeons to physicians to bedside care providers—even including the patient and family. Hospital administrators were included for their influence in engaging all departments and support in participation in education, compliance, and evaluative efforts. The study noted that the 4 Es model had been associated with “significant and sustained reductions in HAIs.”5

Study demographics included 105 (84%) studies from high-income countries and 20 (16%) low- and middle-income countries.5 The studies included a pediatric population (12%) and mixed adult and pediatric populations (88%). Surgical specialties included cardiothoracic (21), orthopedic (22), obstetrics and gynecology (13), gastrointestinal (23), neurosurgery(3), plastic surgery (2), multiple specialties (28), and undefined specialties (13).5

Of the 70 studies that provided compliance with SSI prevention measures, 95% reported an increase in compliance with prevention measures.5 A total of 88 studies reported significant decreases in SSI, and 103 studies used multifaceted strategies to promote compliance to prevention measures. Appropriate use of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis was reported in 86 of the 125 studies (68%) and in 20 (70%) studies in low- and middle-income communities. Other prevention measures used included surgical site preparation (31%), hair removal techniques (25%), normothermia (20%), glycemic control (18%), wound care (17%), preoperative bathing (16%), operating room discipline/traffic (14%), instrument sterilization (13%), hand hygiene (11%), preoperative cleansing (14%), and gloving techniques (8%).5

Borlaug encourages IPs to meet with surgical teams and providers, have a presence in operating rooms, and observe procedures firsthand. She notes that asking surgical teams to educate IPs on their processes helps them understand the knowledge, skills, and procedures used in surgery and that this interaction not only improves and increases participation in teams but also helps IPs become educated on specific surgical issues amid the large scope of care infection control covers.3

CONCLUSIONS

To effect positive changes to SSI incidence, attention must be driven by multidepartmental support, including all chains of command from hospital administration to the surgical team, hospital care teams, outpatient surgeons, physician clinic office care, and patient and family engagement. Although some interventions are diagnosis specific and procedure driven, the global strategies of SSI prevention have the potential and opportunity to affect every aspect of care, from prehospital through inpatient care and procedures to posthospital outpatient care, and must address as many intrinsic and extrinsic factors via evidence-based interventions as possible.

To improve compliance of hospital providers, we must also improve educational and engagement efforts that support evidence-based research that has proved beneficial in decreasing SSI incidence, which in turn improves patient outcomes, decreases health care costs, and improves compliance with Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services policies and patient satisfaction. Designated roles and engagement plans can help address multidimensional needs and patient care factors of providing evidence-based research information and metrics, education, and engagement to follow for outcomes management.

References

- Edmond MB, Wenzel RP. Infection prevention in the health care setting. In: Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. Elsevier Inc; 2015: 3286-3293.e1.

- Ban KA, Minei JP, Laronga C, et al. Executive summary of the American College of Surgeons/ Surgical Infection Society Surgical Site Infection Guidelines-2016 Update. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2017;18(4):379-382. doi:10.1089/sur.2016.214

- BorlaugG.Surgicalsiteinfectionprevention:isthereaplacefortheinfectionpreventionistonthesurgicalcareteam?EloquestHealthcare.August28,2019.AccessedMarch3,2022.https://eloques-thealthcare.com/2019/08/28/ssi-prevention/

- Anderson DJ, Podgorny K, Berríos-Torres SI, et al. Strategies to prevent surgical site infections in acute care hospitals: 2014 update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(suppl 2):S66-S88. doi:10.1017/ s0899823x00193869

- Ariyo P, Zayed B, Riese V, et al. Implementation strategies to reduce surgical site infections: a systematic review. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2019;40(3):287-300.doi:10.1017/ice.2018.355

With 60% of surgical site infections estimated to be preventable, IPs hold a key prevention role in patient safety.

April 19, 2022 Audrey Friedman, RN, CLNC